Tagged: New Hollywood

Great Movies – The Conversation (1974)

Director: Francis Ford Coppola

Starring: Gene Hackman, John Cazale, Allen Garfield, Frederic Forrest, Cindy Williams, Michael Higgins, Elizabeth MacRae, Teri Garr, Harrison Ford, Robert Shields, Robert Duvall

Francis Ford Coppola was flying high in the 1970s. Balancing incredible critical and popular acclaim, Coppola achieved a level of influence in Hollywood that few if any have equalled. In the middle this decade in which he directed three of the most celebrated classics of the American cinema – The Godfather, The Godfather Part II and Apocalypse Now – he also directed a small, personal film called The Conversation. This film, one of Coppola’s few original screenplays, represented the kind of small, personal filmmaking that he had always envisioned his career consisting of before it was side-tracked by the enormous success of The Godfather. As such Coppola consistently cites The Conversation as his favourite of his films.

Francis Ford Coppola was flying high in the 1970s. Balancing incredible critical and popular acclaim, Coppola achieved a level of influence in Hollywood that few if any have equalled. In the middle this decade in which he directed three of the most celebrated classics of the American cinema – The Godfather, The Godfather Part II and Apocalypse Now – he also directed a small, personal film called The Conversation. This film, one of Coppola’s few original screenplays, represented the kind of small, personal filmmaking that he had always envisioned his career consisting of before it was side-tracked by the enormous success of The Godfather. As such Coppola consistently cites The Conversation as his favourite of his films.

Fascinated by technology and process, Coppola first came up with the concept behind The Conversation in the late 1960s after reading a Life magazine article about a surveillance technician who worked in San Francisco. Coppola thought it would be interesting to fuse this character with elements of Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up, a European art film which had been become a surprise box office hit in the US in 1966. The resulting film was a unique, disturbing and intelligent thriller.

Harry Caul, a wire tapper, the best in the business, is hired by the director of a large company to record a lunchtime conversation between a young man and woman in San Francisco’s busy Union Square. The contents of the conversation are seemingly innocuous until Harry uncovers a previously obscured line – “He’d kill us if he got the chance” – which changes everything. Are these young people in danger? Is it Harry’s employer who is a threat to them? As a professional, Harry doesn’t allow himself to get emotionally involved in his work. He tells his partner, Sal, “I don’t care what they say. I just want a nice, fat recording.” But as desperate as Harry is to believe that statement is true, he carries a heavy burden of responsibility for what is done with the information he provides. A job he did years earlier when working on the East Coast resulted in the three people being murdered, including a mother and child. Despite his outward denial of culpability, Harry is racked with guilt. When the tapes are stolen, and he is faced with the possibility that he could end up with blood on his hands again, Harry becomes determined to intervene.

With The Conversation, Coppola wanted to make a film about a character that would usually be peripheral. Thus we have Harry Caul. He is the type of character who we would expect to appear anonymously in one or two scenes in a film, listening in to a phone conversation, perform a function and then vanish from the story. But here he is our protagonist. Harry has devoted his life to his unique line of work which has, as you might expect, left him obsessively protective of his own privacy. This impacts his ability to have genuine friendships and relationships with people, no matter how much he might long for them. He is an isolated and introverted man. Gene Hackman, himself appropriately ordinary looking, is tremendous in the role with a much more restrained and low key performance than is usually his style.

By far the most striking stylistic element of the film is its creative use of sound. Legendary sound designer Walter Murch created a prominent soundscape which plays a pivotal role in the narrative of the film, as well as establishing its uneasy tone. In the film’s masterful opening scene, shot by Haskell Wexler (the rest of the film was shot by Bill Butler), we see the conversation in question taking place in the crowded square as Harry’s team manoeuvre themselves to get their coverage. While the vision places us in the square with the players, the audio we hear is from the perspective of the various rooftop microphones. So there are elements of the conversation which are obscured to us on first viewing, replaced by the digital distortion of microphones. As Harry processes the recordings, we hear different excerpts of that conversation repeated again and again throughout the film. The recording comes to serve almost as a soundtrack for the film. As Harry replays the conversation over and over I his mind, the recording starts to interact with the visuals of the film: as Harry lies on his cot, we hear the woman in the recording commenting on a homeless man lying on a bench; as the prostitute Harry sleeps with leans in to whisper something in Harry’s ear, we hear the woman in the recording say “I love you.” Murch described this relationship as being almost musical.

For those familiar with Antonioni’s film, the influence of Blow-Up is obvious. Blow-Up told the story of a London photographer who discovers that he has inadvertently photographed a murder. The centrepiece of Blow-Up is a scene in which the protagonist, David, is developing his prints and, noticing details in them, he starts to expand them – blowing them up – to reveal what has happened. This scene is reflected in The Conversation where we watch Harry pouring over his recording, tweaking it and stripping it back until he reveals the pivotal line. Like most appropriations of European art cinema devices and narratives by US filmmakers, Coppola uses it as part of a much more conventional mystery narrative. Coppola largely puts to one side Blow-Up’s thematic focus on perception and reality in favour of an exploration of conscience and responsibility.

Like all of the best thrillers, The Conversation features a great twist: a moment when everything we thought we knew is turned on its head. And it is only appropriate that in this film sound should be key to that moment of revelation. After Harry discovers the director of the company, his employer, has been killed he is confused. It doesn’t make sense. As he has done the whole way through the film he thinks over the recording of the conversation and we hear a line which we have heard numerous times before, but this time delivered with a slightly different emphasis. “He’d kill us if he got the chance” becomes “He’d kill us if he got the chance.” It is subtle and brilliant and straight away we know what has happened. Everything falls into place. While this final revelation comes in a single moment, the beauty of The Conversation’s twist is in the deft way that it is set up throughout the film. It is all as a result of a very clever use of point of view. Walter Murch, who also served as the film’s supervising editor, describes The Conversation as having “one of the great unreliable narratives in film.”

The entire narrative is delivered to us from Harry’s perspective. Hackman’s character is in every single scene in the film. We are either watching him, or we are watching what he is watching. It is classic restricted narration. As viewers, we are only privy to the same information as our protagonist. We only know what he knows, we only see what he sees, and importantly, we only hear what he hears. Coppola and Murch use this point of view to trick the audience. Throughout the film, as Harry listens over and over to the recording, the film shows us vision of the original conversation, though these are not necessarily the same shots that we saw in the opening scenes. Piecing these images together with the repeated recording, we are inclined to interpret them as flashbacks, and therefore understand them as being objective. However, they are not objective, they are subjective. This is because they are not flashbacks at all. Rather, they are Harry’s recollections or Harry’s interpretations of what he is hearing. So the first time we see the “He’d kill us if he had the chance” vision, we are seeing something which didn’t actually happen. The visuals are imagined by Harry to accompany his misinterpretation of the sound. But, interpreting them as objective flashbacks, we don’t question them for a second. We heard it too. We just don’t realise that we are hearing it the way Harry hears it rather than the way it was actually said. It is subtle, but incredibly effective in leading us down a path and then setting up the reveal late in the film.

As well as functioning as an intelligent thriller, The Conversation is an important product of its time. The 1960s and early 1970s had seen a number of quite prominent events occur in the US which fostered an uneasy sense that oppressive forces were at work against individual liberty. For the first time in history, the US citizenry began questioning the trustworthiness of its government and institutions. President Kennedy had been assassinated in Dallas in 1963 and people had been left dissatisfied by the findings of the Warren Commission. The Vietnam War was a wildly unpopular conflict, and revelations in the Pentagon Papers that the US had enlarged the scale of war by knowingly bombing Cambodia and Laos compounded the venom. The Watergate scandal started with a break in at Democratic National Committee headquarters in 1972, escalated with revelations of bugged offices and other abuses of power, and resulted in dozens of convictions and the resignation of President Nixon in 1974. Add to these the revelations about US involvement in coups and assassination attempts abroad, and the public were losing faith in their government.

Out of this tumultuous political context arose a cycle of thrillers in the mid-1970s which were notable for their pervading sense of paranoia and their interest in conspiracy, both government and corporate. At the heart of this group of films were Alan J. Pakula’s trio Klute, The Parallax View and All the President’s Men, but the cycle also included the similarly themed Executive Action (David Miller), Three Days of the Condor (Sydney Pollack), Killer Elite (Sam Peckinpah) and Network (Sidney Lumet). With its pervading sense of paranoia and its focus on surveillance technologies, The Conversation was right at home in this very topical group of films. Released just a few months before Nixon’s resignation, The Conversation explored the moral ambiguity of surveillance and the limits of personal responsibility. Yet despite falling bang in the middle of this group of films, and seemingly drawing on the same societal anxieties, The Conversation actually predates the cycle. As mentioned earlier, the film was conceived of almost a decade before it was released, well before the revelations of Watergate. Coppola himself has actually stated, “I never meant it to be so relevant… I almost think the film would have been better received had Watergate not happened.”

Obviously The Conversation was dwarfed by Coppola’s other monumental achievements in the 1970s, and it failed to make a big impact at the box office, though it did manage to make $4.4 million at the box office off a budget of only US$1.6 million. It did, however, win the Palme d’Or at the 1974 Cannes Film Festival and was nominated for three Academy Awards in one of the strongest ever fields: Best Picture (which it lost out to Coppola’s other film that year, The Godfather Part II), Best Original Screenplay (in which it was pipped by Robert Towne’s script for Chinatown) and Best Sound (where it lost to the far less subtle Earthquake), and it remains one of the decade’s best films and one the true gems to come out of the Hollywood Renaissance period.

Great Movies – The Graduate (1967)

Director: Mike Nichols

Starring: Dustin Hoffman, Anne Bancroft, Katharine Ross, William Daniels, Elizabeth Wilson, Murray Hamilton

The late 1960s and early 1970s saw something unusual happen in the American cinema. A number of factors converged to create a window of opportunity for a different type of cinema to emerge from the Hollywood studios. For a period of just under a decade there was a mainstream American art cinema, with Hollywood studios producing youth-oriented films which borrowed stylistically from the art cinema of Europe and took advantage of recent changes in censorship laws to push the boundaries of sex, drugs, nudity and violence. This period, which came to be known as the New Hollywood or the Hollywood Renaissance, would provide some of the most celebrated films in the history of American movies, one of the best of which is Mike Nichols’ The Graduate. Together with another 1967 film, Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde, it marked the starting point of the New Hollywood period for most critics and film historians.

The late 1960s and early 1970s saw something unusual happen in the American cinema. A number of factors converged to create a window of opportunity for a different type of cinema to emerge from the Hollywood studios. For a period of just under a decade there was a mainstream American art cinema, with Hollywood studios producing youth-oriented films which borrowed stylistically from the art cinema of Europe and took advantage of recent changes in censorship laws to push the boundaries of sex, drugs, nudity and violence. This period, which came to be known as the New Hollywood or the Hollywood Renaissance, would provide some of the most celebrated films in the history of American movies, one of the best of which is Mike Nichols’ The Graduate. Together with another 1967 film, Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde, it marked the starting point of the New Hollywood period for most critics and film historians.

The Graduate tells the story of a disillusioned young man who returns home from college and commences an affair with the wife of his father’s business partner only to then fall in love with her daughter. Produced for $3m, it would become the highest grossing film of 1967, taking $49m at the US domestic box office. The key to its success was its ability to tap into the burgeoning youth market at a time when Hollywood’s traditional audience demographic, the family, had become less dependable. One audience survey found that 96% of viewers of The Graduate were less than 30 years of age. 72% under 24. The Graduate was a film which spoke to the Baby Boomer generation through its thematic content, its sexual frankness, its visual style and its use of music.

Thematically, The Graduate is about the head on collision between two generations. Benjamin’s parents are post-war parents. They know what they want from life and they’ve fought for it. Benjamin is a Baby Boomer. He has come into a readymade world and doesn’t know where he fits into it. He represents a youth that are dreaming about a future that they haven’t yet defined. Trying to explain this to his father Benjamin states, “I want my life to be… different.” He doesn’t know what he wants but he knows it isn’t this.

Benjamin represents the burgeoning counter-culture. New Hollywood cinema is full of counter-culture characters, but usually when we think of them we are drawn to the extremes – the long haired, drug taking, hippies of Easy Rider for example. These are characters that consciously identify themselves as being something different. Benjamin doesn’t have than self-awareness. However, in his unwillingness to simply accept the world as it is, even though he doesn’t yet know what he wants it to be, he becomes the counter-culture figure. Not just a counter-culture figure, but a more identifiable counter-culture figure for the vast majority of viewers. Benjamin is an alienated character. Again, it is a different type of alienation to what we saw in other films of that year (Bonnie and Clyde, Cool Hand Luke), but likely an alienation which is more in line with what a lot of young, middle class Americans were experiencing.

Hoffman’s performance in The Graduate is fantastic. He so perfectly encapsulates the awkwardness and uncertainty of a young man who doesn’t know who he is. He underplays the character beautifully, whispering rather than speaking, nudging rather than moving. Until Elaine comes into his life he doesn’t do anything with conviction.

Given how iconic Hoffman’s performance has become, it is interesting to note that he was not the obvious choice for the role that he seems to us now.

In the 1963 Charles Webb novel from which the film was adapted, the central characters are all WASPs (White Anglo Saxon Protestants). Benjamin is described as a blonde haired, blue eyed, six foot tall athlete, “a surfboard” is how co-screenwriter Buck Henry described him, and a far cry from the Benjamin we come to see on the screen. It was originally Nichols’ intention to stick with this vision. His vision for the film saw Benjamin being played by Robert Redford, Elaine by Candice Bergen and Mrs. Robinson by Doris Day. While Doris Day turned down the part as it “offended [her] sense of values,” both Redford and Bergen read for the parts.

But Nichols’ instincts told him something was off. He explained, “When I saw the test I told Redford that he could not, at that point in his life, play a loser like Benjamin, ‘cause nobody would ever buy it. He said, ‘I don’t understand,’ and I said, ‘Well let me put it to you another way: Have you ever struck out with a girl?’ And he said, ‘What do you mean?’ It made my point.”

Hoffman had done a screen test for the part and despite not being the look they had been envisioning, all present were in agreement his test had been the most interesting. So Nichols’ made the decision to change the family from WASPs to Beverly Hills Jews and cast Dustin Hoffman. Rather than the strapping, stereotypical All-American boy that Benjamin was written to be, Hoffman became a sort of genetic throwback in the family line.

Prior to The Graduate Hoffman had done nothing of significance on screen. His only screen credit was 19th billing in Hap (1967). But Buck Henry had seen him on stage in a play called Harry Noon and Night in which he played a crippled, German transvestite. Henry said his performance had been so brilliant it was impossible to believe he wasn’t at least one or two of those things.

The casting of Hoffman over a young star like Redford was a big deal, with potentially huge financial ramifications, but it paid off handsomely, as Hoffman’s performance earned him the first of his seven career Best Actor Oscar nominations.

It should also be noted that the casting of Anne Bancroft was significant, given she was only six years older than Hoffman, but the two worked superbly together. The power relationship between Benjamin and Mrs. Robinson in the first half of the film is just brilliant comic acting. Mrs. Robinson is the polar opposite to Benjamin. She knows what she wants. She is authoritative and self-assured, although later we come to see her vulnerability. The power relationship between the two is perfectly demonstrated by the fact that at even their most intimate moments, Benjamin still calls her “Mrs. Robinson.”

The casting of Hoffman was representative of a greater trend in casting that would take place in the New Hollywood era. In the studio era, the industry operated largely on the understanding that people wanted escapism. They wanted a sense of distance between their own lives and what they saw on the screen. Baby Boomers, on the other hand, wanted to be able to engage with the movies. More to the point, they wanted the movies to engage with them. They wanted to see truth and reality up on the screen. So the New Hollywood period saw the arrival of a number of new faces, not just in the sense that they were new to the industry, but also in the sense that they were a different type of face to the faces we were used to seeing on the screen.

The New Hollywood period introduced a new type of movie star. A star that looked like an average Joe. Alongside Dustin Hoffman, the generation of actors who rose to prominence in this period of Hollywood’s history included Robert De Niro, Al Pacino, Richard Dreyfuss, Gene Hackman, Robert Duvall, James Caan, Harvey Keitel, John Cazale, Christopher Walken and Elliot Gould. These actors banished the vanilla features of the studio era in favour of a gritty realism and ethnicity.

The same was true to a certain extent for actresses, with new beauties like Jane Fonda, Meryl Streep and Faye Dunaway being joined by more normal looking actresses like Diane Keaton, Ellen Burstyn, Sissy Spacek and Shelley Duvall. Obviously, there remained a gender double-standard which says it is harder for an unattractive woman to become a movie star than an unattractive man, but none the less these actresses displayed a different look to the wholesome pertness of a Doris Day in the 1950s, or the studio era bombshells like Marilyn Monroe or Rita Hayworth.

Appealing to the youth audience in the late 1960s didn’t just involve telling young people’s stories, it involved telling them in a style which appealed to young people. This youth demographic that had been shunning traditional Hollywood fare were enthusiastically consuming foreign films, particularly the European art films. 1966, the year before The Graduate was released, was the highest grossing year for foreign films at the US box office. Much of that was due to the success of Blow Up. As Stanley Kramer put it, “Everyone in Zilchville [saw] Blow Up, not just the elite.”

European art films like Blow Up and, in particular, the French New Wave films of Godard, Truffaut, Rohmer and Chabrol, introduced a new style of cinematic storytelling. Where the studio era had always operated on a principle of invisible style, the French New Wave saw cinematography and editing as narrative tools. Filmmakers employed an unconventional visual style which drew attention to itself, in complete opposition to the principle of seamlessness.

Mike Nichols was a fan of New Wave filmmaking, as well as the later Italian neo-realists like Antonioni and Fellini. So in The Graduate we see a lot of non-traditional Hollywood cinematography and editing, giving the film a very contemporary look. But, like with the European films, this contemporary look was not just style for style’s sake. It was not simply a cynical imitation of what was popular at the time in order to make the film marketable. In The Graduate visual style, as well as music, is used for narrative purposes, primarily through emphasising tone and visually representing emotions.

For an example of this, let’s look at a few of the different ways that Benjamin is shot.

Firstly, consider his positioning in the frame. Early in the film Benjamin is rarely centred in the shot composition. Instead he is largely situated to the right of the screen with expanses of space to his left. It is only later in the film, once he has met Elaine and found a sense of purpose and that his character possesses the conviction to dominate the image.

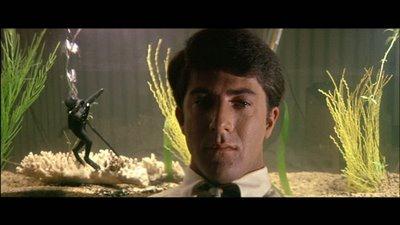

Secondly, on a few occasions the camera adopts Benjamin’s subjectivity, often as a means to demonstrate his claustrophobia in the suburban world of his parents. This is, of course, most notable is the scene in which a reluctant Benjamin is forced to model his new scuba suit for his parents’ friends. For this scene we see the world through Benjamin’s scuba mask – as well as hearing the muffled audio and his breathing. This same sense of claustrophobia is stylistically represented in a different fashion at the first party scene, the welcome home, through the use of very close shots of Benjamin’s face with other faces squeezing their way into the frame.

Thirdly, Nichols makes use of zooms. Using a zoom shot was traditionally considered bad filmmaking. However, Nichols uses zooms at a number of points throughout the film for particular emotional effect. When Nichols zooms out, it is to emphasise the isolation of a character (the opening shot of Benjamin in his seat on the plane). When he zooms in, it is to take us into their soul (this strategy is employed later in the film with Mrs. Robinson as we start to discover more layers to her character).

The stylistic influence of the French New Wave extended to the editing. Like the New Wave filmmakers, Nichols chooses at times to abandon the principles of classic continuity editing in order to use his cutting as a narrative or emotive device. Two particular moments come to mind.

The first is the moment when a naked Mrs. Robinson corners Benjamin in Elaine’s bedroom. In a reflection on a portrait of Elaine, we see Mrs Robinson sneak into the room unbeknownst to Benjamin. As the door bangs shut behind her, Benjamin spins. Nichols breaks his turn down into three different shots, exaggerating the movement through editing. We see his face in an over-the-shoulder shot as he looks at Mrs. Robinson. He is panicking and this panic is reflected in the cutting of the scene. As Mrs. Robinson propositions Benjamin, the over the shoulder shot is interrupted by five very short flashes of different parts of her naked body. Quick glances, like those of a panicking young man who doesn’t know where to look. In all, there are 15 cuts in this very short moment between her entering the room and him running away downstairs. This rapid cutting emphasises his panic in that moment, and is beautifully juxtaposed by the calm, measured way in which Mrs. Robinson speaks.

The second I call the “Out of the pool and onto Mrs. Robinson” transition. We see Benjamin in the pool. He goes to pull himself up onto his lie-lo, and the motion that starts with in the pool finishes with him on top of Mrs Robinson. While lying on top of her we hear his father’s voice, which brings us back to the pool. This one cut works almost like an entire montage in itself. This is Benjamin’s life at the moment: lying in the pool and meeting with Mrs Robinson.

One of the primary ways in which The Graduate aligns itself with the youth counterculture of the time is through its soundtrack. Rather than a traditional orchestral score, Nichols employs the songs of folk duo Simon and Garfunkel, with the resulting soundtrack being one of the most striking features of the film. The use of popular music in the place of a traditional score was a recent innovation. Richard Lester’s two Beatles films, A Hard Day’s Night (1964) and Help! (1965), had employed the group’s music to great effect, and films like The Graduate, Easy Rider and American Graffiti would see the popular music score become a prominent feature of the New Hollywood period.

Nichols had always wanted Simon and Garfunkel for the soundtrack. They had risen to prominence in 1965 with their hit single ‘Sounds of Silence,’ and were strongly identified with the counter-culture movement that was bubbling up in the 1960s in America.

While the majority of Simon and Garfunkel songs used on the soundtrack were pre-existing, the producers made a deal with Paul Simon to provide them with three new songs. However due to a busy touring schedule, Simon did not get around to writing the agreed upon songs. When Nichols pleaded with Simon to show him something new, he played him a bit of a song he had been working on about time past, about Joe DiMaggio and Eleanor Roosevelt. Nichols persuaded him to change it from Mrs. Roosevelt to Mrs. Robinson and the song made its way into the film. Paul Simon only recorded as much as appears in the film. The producers of the film wanted him to write the rest so they would have a promotional tie-in, but Simon was reluctant. However, the movie becoming a big hit was enough to persuade Paul Simon very quickly wrote and recorded the rest of the song. So, for any Simon and Garfunkel fans out there, this accounts for why the version of ‘Mrs. Robinson’ that appears in the film sounds significantly different to the version which was released as a single.

As well as providing an iconic score and serving as useful cross-promotion for both the band and the film, Nichols used Simon and Garfunkel’s music to very specific narrative purposes. Musically there are three distinct stages through the film. In the first third of the film we hear ‘Sounds of Silence’ again and again. It becomes the theme for Benjamin’s uncertainty as he ponders his future while in the suburbs. In the second third of the film the music changes and the song ‘Scarborough Fair/Canticle’ becomes very prominent. It is the theme for Benjamin’s pining after Elaine after she discovers about him and Mrs Robinson. For the final third of the film we get the much more upbeat ‘Mrs Robinson,’ it’s faster tempo marking Benjamin’s newfound determination as he pursues Elaine and seeks to rescue her from her upcoming marriage. And the payoff for this aligning of different tunes with different states of Benjamin’s psyche comes in the film’s final scene.

The conclusion of Nichols film is masterful, and gives us a number of things to consider. As we watch Benjamin and Elaine ride away together, it is tempting to assume that we have just witnessed a standard Hollywood, happily-ever-after conclusion, but in fact nothing is that straight forward. For starters, Benjamin doesn’t actually succeed in stopping the wedding. He arrives to see Elaine kissing her husband. The vows have already been exchanged. As Mrs Robinson points out, “It’s too late.” So what does this mean for Benjamin and Elaine running away together, knowing that legally she is married? The way Nichols concludes the film leaves us with great uncertainty about the future of these characters, and that uncertainty is communicated through two subtle directorial decisions. Firstly, we watch them run onto the bus and sit down together giddy with excitement, but the camera stays with them long enough to watch the adrenaline die down and their faces go blank. Secondly, the music that accompanies the bus driving away is ‘Sounds of Silence,’ the song which we have been encouraged to associate with Benjamin’s insecurity and uncertainty about his future. Had Nichols cut that shot while they were still smiling and shown the bus driving away to the up-tempo rhythm of ‘Mrs. Robinson’ you would have had a perfect feel-good ending. Instead, through two subtle choices the director allows for ambiguity and uncertainty, leaving his audience with something to ponder.

In 1998, the American Film Institute marked the centenary of American cinema by releasing a list of the 100 greatest American films, with The Graduate coming in at #17. Despite coming from a period that delivered a number of truly remarkable pieces of American cinema, The Graduate still stands out as a fine achievement. Hilariously funny but still undeniably authentic, it is undoubtedly one of the finest youth movies ever made.

By Duncan McLean

You must be logged in to post a comment.